The Flavor of Modern Irish Cuisine

Green. This is the word that comes to mind when you encounter Ireland. Green and lush. It's what we sensed when we first stepped into St. Stephen's Green, a tree-filled public park in the center of Dublin on an unusually warm late June afternoon. This park is also hallowed ground for the Easter Rising of 1916 and for being the front lawn to the Shelbourne Hotel where the Constitution of the Irish Free State was written in 1922. But on this day it would be the place for a picnic, celebrating our first day in Ireland and hosting our first tastes of this welcoming country.

Earlier in the day my husband and I had set out for a walk through the center of Dublin and came upon a cheesemonger called Sheridans. I'm not sure which inspired our picnic more, St. Stephen's Green or the farmhouse raw milk cheeses that lined Sheridans shelves. Tucked a few steps off of Grafton Street, one of Dublin's main drags, Sheridans also has shops in Galway, Waterford and Meath. Sampling tastes and the names of farms were offered generously by men handsomely tailored in dark navy and white aprons, and we bought more than a picnic could consume, our bag filling with wedges of Durrus, a semi-soft washed rind cow cheese that smelled of hay, a pungent Boyne Valley Blue from County Louth made of goat's milk, and a Gubbeen cured, spiced, and lightly smoked chorizo produced by Fingal Ferguson in West Cork, using meat from his own pigs. We finished with a half-loaf of a bread that had a tender crumb and complex flavor, made with Ireland's remarkably fine organic flours, and conceded to a bottle of a decent Chianti.

It turned out that our Dublin picnic was just the beginning of our Irish food adventure.

A Quiet Food Revolution

The foods of Ireland, like those of England and the rest of the U.K., have long been a culinary punchline.

Some have been childish and insulting, as in, What's an Irish seven course meal? A six-pack and a potato. Other clichés are seasonal, as with green bagels and inedibly salted corned beef and overcooked cabbage for St. Patrick's Day. Still others are theatrical flash points, like the demeaning feedings of lumpy Complan, a 1950's powdered energy drink, in playwright Martin McDonagh's shockingly unsentimental Beauty Queen of Leenane (a favorite of mine and regrettably, no relation).

It is not unfair to associate Irish food with poverty, a view easily shaped not only by McDonagh's works but also such books as Frank McCourt's Angela's Ashes where the drink took the grocery money, or by driving narrow roads of counties Galway or Clare where there is mile after mile of the 19th century "famine walls," built with field stones by starving laborers who were paid with scraps of food. But these images are of Ireland's past.

Today Ireland's cuisine is defined by some of the finest ingredients in the world that until recently were mostly shipped to other countries' kitchens, especially in England and France. Happily, more of that bounty is now staying home and inspiring Irish chefs and cooks who quietly favor its remarkable flavor more than the flash of culinary celebrity.

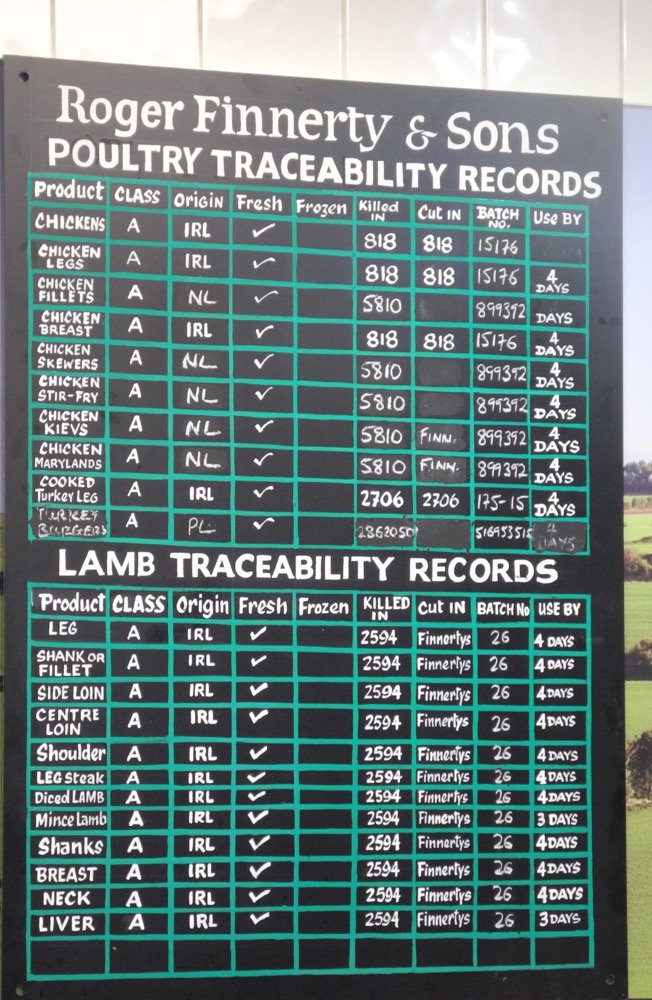

After that picnic in St. Stephen's Green, my husband and I spent nearly two weeks zigging and zagging across Ireland. And we ate. We tasted tender lamb and beef, and saw how in butcher shops, pubs and restaurants, the name of the farmer who raised each animal and can account for every meal and hour of its sleep, is prominently posted. We had farmstead cheeses, made with sheep, cow and goat's milk, produced in small lots, often from raw milk, that can rival any French prix du fromage. Wheat grown in organic fields in counties Louth and Kilkenny, where not a speck of trash litters its wind bent stalks, is then stone-milled in small batches and baked into tender soda breads and hearty multi-grained wheaten breads. There were sweet cockles and periwinkles from Dublin Bay and on the west coast, pure white hake from the frigid north Atlantic. We tasted game and fowl and eggs with yolks the color of the sunflowers that rimmed the grazing fields. And oh my, the butter, the butter -- high in butterfat, sometimes sweet and sometimes with the crunch of sea salt.

All this may seem a culinary postcard but it is real. A small country, Ireland has slightly less acreage than South Carolina, with an entire population that is a touch below 4.6 million, of which a quarter live in Dublin. This means most of the country is rural, with some of its landscape surfaced with stone resembling a moonscape and much of the rest covered with green fields rolling for mile after mile. Sixty-four percent of the land is used for agriculture and 98 percent of its 140,000 farms, which have an average size of less than 100 acres, are still in the hands of families and not some Irish agribusiness. It can take a few days to fully appreciate that this is not a Pinterest image created by a marketing leprechaun.

How did this happen?

There has been a convergence. First, there is Ireland's surprisingly mild climate and the rich soil of the land. Next, its small population lets mile after mile of land stay free for grazing sheep or for planting fields of wheat. This is a country largely absent of dirty industries, which means it has cleaner air and water. And with the blessing of its citizenry, Ireland's government practices good stewardship of its land and land use practices.

Ireland's traditions run deep but it now also embraces international culture, influenced by travel, immigration, and by becoming part of the EU, which it did in 1973. When Ireland's economy suffered and the Celtic Tiger stumbled in the 00's, much of its younger population sought economic opportunity elsewhere, but as the economy improved, many came home. And when they did, some returned enthusiastically to the farm and the sea and the kitchen.

Combine these circumstances with the fact that Ireland is a society acutely and poignantly tied to its past. The Irish remember the decades, the centuries, when poverty and discrimination left them with little more than family and the comforts of tradition. Perhaps this is why they value a cuisine based on simplicity and local food, a reaction to memories of scarcity and how they survived only because of the land.

Even if you never go across the sea to Ireland, nor visit Galway Bay or any other part of this welcoming and exquisite country -- although I so very much recommend that you do -- we can still be inspired by the ingredients and traditions of modern Irish cooking.

Irish Terroir

The change began with Ballymaloe. Myrtle Allen, now in her early 90s, created Ballymaloe House in Cork in 1964. Her daughter Darina then turned what was a country inn with an excellent kitchen into a world famous restaurant, hotel, and cookery school. Today you can visit it to take cooking lessons, stay for a few days in its charming rooms, or just have a meal in its dining rooms. As an example of the kind of unexpected flavors that come out of its kitchens, we've added a link to a recipe for a spicy Tomato Chile Jam by Darina Allen, shared with me years ago by my friend Roy Finamore.

Artisanal food producers are now across the country, making the most of what nature provides. On Ireland's 1,600-mile western coastline, there is sweet and salty lamb that has grazed on seaweed, mussels farmed in Killary Harbor, rare breed pigs, and Galway oysters. (Read more about Ireland's Culinary Coast in this month's Saveur magazine.)

Still, without ever visiting Ireland, we can nonetheless enjoy the achievements and flavors of Ballymaloe and other Irish food innovators by imitating their principles and practices: be relentless in your search for the best ingredients, buy local as much as possible, know where your food is coming from, and understand its terroir.

Today there are dozens of cookbooks about Irish cooking, including several excellent ones from Darina Allen, but here are three recent ones that will help you engage with Ireland's new spirit while discovering its precious past.

Clodagh's Irish Kitchen

Clodagh McKenna is a native of Cork, the author of five cookbooks, a chef and restaurateur, and an advocate for the Irish cooking renaissance. She's been often compared to Rachel Ray, on whose TV program she regularly appears, but I'm not sure that really captures Clodagh. While she is lovely and charismatic, her enthusiasm is combined with serious cred having been trained in Ballymaloe's kitchens as well as ones in France and Italy. Her latest book, Clodagh's Irish Kitchen (published by Kyle Books, © 2015, hardcover with color photographs, 256 pages, $29.95), makes the case for how Irish cuisine is at its best when it combines local ingredients and traditions with global flavors and techniques.

She begins with a chapter on Weekend Baking including Thyme-Herbed Soda Bread and an irresistible black-as-stout iced Guinness Cake. Her Breakfast choices start with Green Goddess Juice and finish with Full-Irish Breakfast. The chapter on Midweek Suppers has eight soups and chowders, her version of a traditional Coddle, plus salads and mussels and Pies of Fish, or Beef and Guinness, or Shepherd's Pie with Colcannon Topping, a classic but the best I've ever made Lamb Stew (she has you add barley which is a brilliant touch), and with an Italian twist using a famed Irish cheese, there is Cashel Blue, Caramelized Onion, and Thyme Pizza. The nine chapters continue with recipes for An Irish Dinner Party, Sunday Lunch, desserts, and finally Preserving the Season with jams and chutneys.

The book has 125 recipes, a pretty blue ribbon placeholder, engaging color photos of plated food and Irish landscapes, and an inspiring last chapter about what she calls Tablescaping but what I took away as the fine details, including menu planning and creating a beautiful environment in which to present what you cook, especially at special and holiday meals.

We had difficulty choosing two recipes to share with you but finally settled on Summer Lamb with Fennel and Roasted Nectarines for how she showcases one of Ireland's favorite ingredients, and Beet, Blood Orange, Irish Goat Cheese and Hazelnut Salad, which is a splendid flavor combination that you'll particularly love mid-winter when citrus is best. See our links to both recipes.

Clodagh is completely present on every page of this book. You hear her voice, learn from her point-of-view and helpful guidance, and become at ease from her enthusiasm, just as she is when you meet her in person. I had the pleasure of recently talking with Clodagh about modern Irish cooking and I hope you will pause to listen to her passion for her Irish kitchen in our podcast. See our link to listen.

The Best of Irish Country Cooking

This is Dublin writer Nuala Cullen's fourth book about Irish food and it is splendid. With 100 recipes and almost as many gorgeous photographs of both recipes and landscapes, The Best of Irish Country Cooking (published by Interlink Publishing, © 2015, hardcover, 176 pages, color photographs, $35.00) captures the time-honored and the modern of contemporary Irish cuisine.

While acknowledging Ireland's legacy of hearty food, Ms. Cullen showcases how to make tempting use of the new high-quality ingredients that are coming from the Irish food revolution: wild salmon, oysters, marsh-fed lamb, farmhouse cheeses, and small-batch whisky. Many of the recipes begin with a brief historic headnote, as when she explains the origins of Potted Salmon or Roast Michaelmas Goose With Prune, Apple, and Potato Stuffing. But she does this not to make the book a history volume but instead to pull us into the rural traditions of this cuisine that have led to today's flavors.

There are seven chapters: appetizers, soups, mains, salads and sides, baking, and preserves. There are classics like Spiced Beef, Corned Beef and Cabbage, and Christmas Pudding, but there are also new ways to cook the ingredients that Ireland may know best, such as Stuffed Pork Chops With Potato Apple Fritters or Hake Baked in Paper or Celery Soup With Blue Cheese.

We're sharing a classic recipe and a new take, first with Beef and Mushroom Pie With Guinness and for something sweet, Cherry Mousse (that you can make with either fresh or frozen cherries). See our links.

If you purchase this lovely book you'll want to spend time with it not just for the recipes and the engaging text, but possibly just as much, for the photographs. They might make you book a flight on Aer Lingus.

The Potato Year

The potato was introduced to Ireland in the 16th century and despite the near ruinous effects of the 19th century potato famine with all its economic and political repercussions that expanded the great Irish diaspora, the potato remains a loved and beloved ingredient. In Lucy Madden's newly updated edition of her 1992 book, The Potato Year: 300 Classic Recipes (published by Mercier Press, c 2015, hardcover, 350 pages, $21.00), she first tells us more about this surprisingly complex vegetable and then gives us a year's calendar of ways to cook them, starting with January's Dublin Coddle and ending with December's Potato Diet.

There is much charm in this book. Writer Susan Jane White's foreword is a warm and personal introduction to both Ms. Madden, described as "among the greatest of our country-house cooks," and her book's ambition. This small, beautifully printed volume is published by Mercier Press, a Cork-based publisher that specializes in Irish letters, history, and culture.

While there are no photos, the recipes come with story telling and poetry, as with a very traditional dish known as Colcannon. Ms. Madden's version (see our link) gives us the option of making it with either kale or cabbage, making the point of how the customs of Irish cooking can withstand and even may be bettered by new ideas. So you kale lovers out there, try this tender and comforting dish instead of trying to chew your way through a kale salad.

For everyone else, a reminder that food is both pleasure and political:

The beef and the beer of the Saxon may build up good, strong hefty men;

The Scot goes for haggis and porridge and likes a ‘wee drap’ now and then;

The German may spice up a sausage that’s fit for great Kaisers and Queens,

But the Irishman’s dish is my darling -- a flitch of boiled bacon and greens.

They laughed at the pig in the kitchen when Ireland lay groaning in chains,

But the pig paid the rent, so no wonder our ‘smack’ for his breed still remains,

And what has a taste so delicious as ‘griskins’ and juicy ‘crubeens’,

And what gives health, strength and beauty like bacon, potatoes and greens?

From "Bacon and Greens," by Con O’Brien, 1930

Bain sult as an chócaireacht na hÉireann!*

Kate McDonough

Editor, TheCityCook.com

*Enjoy the Irish cooking!